The entire story, the truth, is always the best story. And I realized that this story needed to be told in full. I’m taking a chance and revealing some rather personal things, because how I got here, and what this means for me, is a story with a message, a lesson. Meaning. Well, at least for me. You might find meaning in it as well. Or at least a little hope.

11,500 words; est. read time 60 minutes

Part 1

The fire burned my camp flat.

I’d lived in that spot for more than six months, and in the roughly square-mile-wide area an entire year. Why on earth was I there?

People I trusted, and whom I felt close enough to consider adopted family, had turned on me in late 2020. The door was shown, with the deadline of March 2021.

Despite the eviction moratorium of Covid, the local government chose to allow my eviction. So I sold what I could, bought a basic uninsulated cargo trailer, and hit the road.

I’d already been spending weeks at a time living on the road as I tried to make a go of doing the whole “YouTuber” thing. Despite throwing years at it and posting more than 250 videos covering a wide array of outdoors topics and locations, I never got monetized. Heck, even today I still haven’t even crossed 500 subscribers.

But I sure tried. Even homeless I kept creating content. Being somewhat accustomed to living in such a manner, it wasn’t quite so bad at first, and I also assumed it would only be a temporary situation.

Over what became more than four years of solo homelessness, I converted the trailer to a basic living space, later had to sell the trailer, made a wholehearted effort to get into running for fitness, kept at YouTube, and just tried to survive while not being a burden on anyone. I never wanted my homelessness to impact society. But there’s a limit to what one can do alone.

I was unfortunate enough to have all kinds of health issues, leaving me pretty much at the limit of my efforts just to stay as functional as I was. Lots of exercise helps, such as for my symptoms which in 2020 I was told likely pointed to MS. I was, however, fortunate enough for those issues to finally have qualified me for disability, and so I ended up living on the paltry sums of monthly SSDI deposits.

Disability is not a get-rich-quick scheme, and I did not intend to rely on the government forever. I wanted to eventually get off disability, earn a decent wage, and have a home again. This was a stopgap until I could get solid ground under me.

I tried. Lord knows, I tried. And still try. Replying to dozens upon dozens of ads for housing. Applying to every assistance program for which I qualified. Doing my best to stay fit and healthy, independent and self-sufficient. But food budgets limit how many calories you can burn off every day doing vigorous exercise. And as we all know, food only got more and more expensive.

There were good days and bad days in terms of health, and many, many bad or even scary experiences in general. I’d been menaced, stalked, harassed, insulted, disrespected, endangered, even shot towards by irresponsible gun users. After several years I was kind of shell-shocked and traumatized. And deeply humbled.

In May 2024, my small truck gave up. On the way up a grade, the engine sputtered, the Check Engine Light flashed repeatedly, and a loud clacking/banging sound came from under the hood. It lived to the point when I parked it 24 hours later in a storage facility, where I already leased a 5×5 unit to keep my belongings safe.

At first I tried backpack life, using the local Dial-a-Ride and hauling fifty pounds of stuff out onto the nearby Deschutes River for a week at a time.

It was a minimal life, but at least I had the equipment and skills. But way too hard on my body. The last trip, I nearly didn’t make the hike back to camp, suffering extreme exhaustion under the load. It was a dicey situation, being unable to hike more than about thirty seconds, and then needing five minutes to recover. I did finally make it, but knew that the next trip could turn out to be physically impossible.

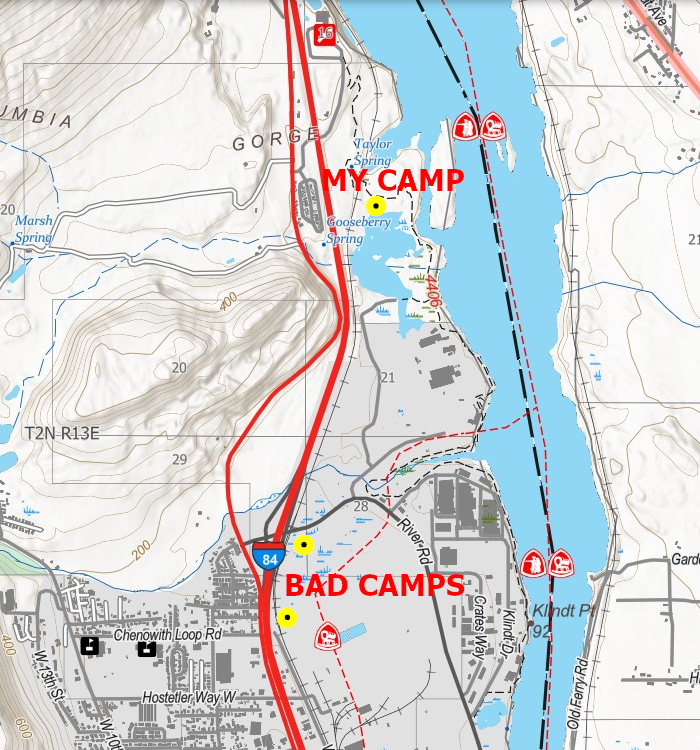

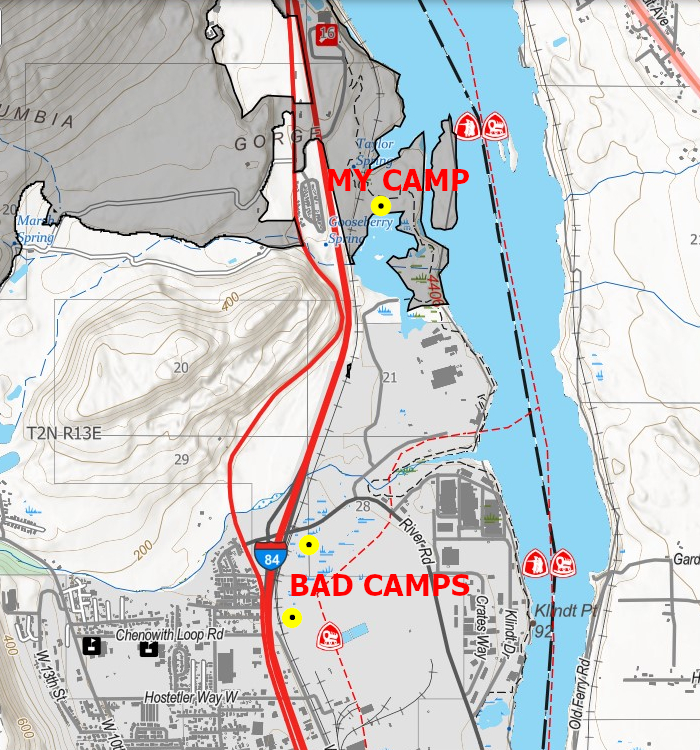

So I gave up on that plan. It looked like I’d have to compromise yet again. I stowed the backpacking gear in the storage unit, walked away with a daypack on, and went into living on the streets of The Dalles. I knew the local area well enough to find a place away from most of the horror encampments, which ran from the end of 2nd street to the River Road overpass.

For the first month or two I slept in tall grass of a natural area near a little beach along the Columbia just off the Riverfront Trail on the west side of town, past the massive Google data centers. Not wanting to do an encampment, I used a military surplus bivy bag, a gift from a hiking buddy a few years back. Its built-in sleeping bag and heavy zippers, combined with woodland camo, were perfect. Some hunks of old memory foam made a barely adequate mattress.

Each morning I bundled them all up tightly, double-bagged them in lawn bags, and stashed them deep in a nearby bush. Then when I returned, undid the whole process. Tedious. It got me a place to sleep at least.

But it was a party zone. No peace. Blasting stereos, barking dogs, screaming kids, yelling adults, jet skis racing by along with speedboats employing hot-rod V8s and massive stereo systems. On weeknights even, and well past dinnertime.

For someone with noise-sensitive severe complex PTSD, it was a nightmare. The final straw came when a group of youths stayed out all night partying on the beach under the guise of “fishing.” I got no sleep.

I moved upriver a quarter mile, finding a large walnut tree with a wide canopy. Flat areas around its base between low branches offered some shade and cover, and the tall grasses around also helped hide my spot.

Still, I wore tan shorts and a drab green shirt, just to help blend in. A mandatory daily hosedown with bug spray, and I slept out on the ground for the rest of summer.

Along the way, I decided to get back to writing. Do what you know, right? At first, I wrote a few magazine-length tales of my outdoor adventures from my YouTube channel, and queried Oregon publications about potentially publishing them. No surprise that everyone ignored me.

So I decided to publish them myself. Using the library’s public computers, I showed up five days a week and spent three or even four hours writing and editing. When I had enough essays and stories to comprise a small book, I laid it out and published it as an eBook, the nonfiction collection There’s Always Ants.

It was my first book, my first published writing in more than fifteen years, and more than three decades since I’d first decided I wanted to be a writer. I was proud, satisfied, and of course, having no editor, horrified to see the few typos sprinkled throughout. I had to laugh; of course my first book would be gloriously imperfect. That’s kind of just how I roll. There is nothing more boring to me than perfection. All those rough edges make things interesting.

Fall started yellowing the leaves and dropping them, and the wind coming off the cool waters of the Columbia started chilling. My cover was going away, and eventually would be gone. I’d have to move on, or be spotted.

You see, I’d grown weary of packing up every morning and then setting up every afternoon, as well as carrying so very much stuff like extra clothes for overnight, or jugs of drinking water.

I refused to be profiled as homeless, so I didn’t risk being seen carrying a load of camping gear back and forth every day. If I wanted more comfort, and especially rain protection, which I’d need any week now, I’d have to do something about better shelter. I’d have to do something akin to an encampment. Yet again, I’d have to compromise.

The months of walking everywhere the bus didn’t go, hauling water, enduring an hour of trudging in terrible heat every afternoon, all combined to make my legs ache badly and my back cry out. I already bear a surgery scar on the back of my neck; eventually more will line my spine as the many issues come to a head. Bad discs, stenosis, arthritis. Pain. Always pain. I really needed to lighten my daily load, not add to it with camping gear.

So I took a cheap tent and tarp out to the walnut tree, and bought some camouflage material to help hide me. The expenditure hurt, but the privacy was wonderful, as was finally keeping bugs off me as I slept. It made me feel a little less homeless, having a “place” to which I could return and have it me mine.

With Ants published, the next thing the writing muse ordered me to get typing was a collection of fictional stories set in the outdoors. Only since I like horror, and certainly know how bad and scary things can get in the outdoors, naturally these four tales would be scary. Or at least “dark.” So I kept my head down and kept working.

In October 2024, I came back to camp to find everything gone.

Well, almost everything. My thermal underwear and some hunks of memory foam I’d used for a mattress were tossed in the bushes. And they didn’t want my half-jug of water.

I’d known such a thing could befall me, but it still stung badly. How cruel, how intrusive, how disrespectful!

Here I was, staying presentable, clean-shaven, clean clothes, no drugs, no alcohol, nor tobacco or vape. Causing not one problem in the community, well-liked by most who knew me. Working every day on my writing, and not even using the soup kitchen or food pantries. I’d never even misspoken to a homeless person, let alone mistreated one. I was not deserving of such an insult, from any caste of society.

And certainly not deserving of being robbed of my home.

I stayed that night in a motel, which was a nice but rare treat. I took full advantage, getting laundry done and recharging a lot of things that seemed to always be low or dead. And being indoors for just one night.

The next day I went back to setting up and tearing down daily, which was physically hard. I still did not enjoy the best health despite my best efforts.

Hunting season had started, and across the small inlet from the walnut tree, some truly obsessed duck hunters started showing up and shooting even before dawn, in near darkness. Their pellets were landing all around me, even striking the tent.

That spot was over with anyway, due to the lack of vegetation. I was no longer hidden. I had to find a new home.

A few days later I bought a pair of hand pruners. And then hiked a few hundred yards south to a blackberry thicket I’d been eyeing.

There was a small inlet in the sea of thorns under some small trees, that was begging for a little hidden sleep spot. I’d have to prune back the tangle of vines. Which I did, taking three hours one day and then three more the next. I bled a lot. But got about an 8×8 area cleared. By the start of November, I was using it.

Then I bought the cheap stuff, a small $40 summer tent, a $40 “zero degree” sleeping bag that was useless below forty-five degrees, a ground cloth tarp, and more camo netting. Some heavy stakes, extra line and tarp clips helped hold it down in the severe winds we get in the eastern Gorge.

I got back to work, publishing Don’t Go Outdoors, the short-story collection.

And then braced myself for winter. I needed a second bag, so I grabbed a twin for the cheapo and nested them inside one another. That helped, but I still needed extra thermals so $40 later I had two sets, which helped further.

But winter. She’s mean east of the Cascades. It was below freezing every night for months. Some cold snaps saw teens or single digits even. Snow blanketed the tent, even coating it so much I nearly suffocated one night. Some snows melted off by the next day. We got a bad storm in February, nearly burying the tent. And coating the region for several days. I hiked two hours through half a foot of snow on those days.

Other times it was soaking downpours or blowing snow on the walk. Always in the biting wind. Which blew right through my summer tent, its walls only bug mesh. I started using three or four HotHands strategically placed around my body to survive the bad nights.

I was still on foot, and so had to hike back and forth, in all weather conditions, the whole 5-mile round trip. Every day. Mornings the worst, so bitterly cold. Winds pulled tears from my eyes and made my nose run constantly. In such extreme conditions, you notice little things. Like the fact that despite hurting my spine, the daypack helped insulate my back from the cold. And kept it dry, using the pack’s rain fly.

Despite the hardship, I endured.

Along the way, the muse spoke to me again, this time demanding without compromise that I throw all my efforts into a weird story about a mentally ill woman who follows her hallucinated voices from northern Oregon to Kalispell, Montana.

I practically became obsessed, toiling nearly seven days a week on it. Mornings at the library editing or rewriting, afternoons doing read-throughs and taking notes for tomorrow’s round of edits.

In January 2025 I finally gathered enough funds to pick up a bicycle. That helped greatly. Now I could get places without spending hours out in the cold. I could ease up the pain on my back by getting a rear rack and some bags. Which I did.

At first I felt so out of shape I pushed the bike up even short hills. But then realized after a few months of biking, and seeing not much improvement, that my fatigue issue was still there, nearly a year after it had nearly stopped me from getting to the backpack camp. it was there, and getting slowly worse. Stairs started getting hard, and I found myself at times gasping for air on the bike. Something was wrong, but without health care and with a strong will to remain independent, I put on a brave face and pushed on.

Winter of course ended, and on its exit spring halfheartedly broke out. In May I came back to camp to find it nearly destroyed. While I was away working on the book, workers took a masticator and mowed down the blackberry thicket that had been hiding me, nearly running over my tent from two directions. They’d come within just three feet.

They left the trees, and the remaining thicket fifteen feet south of me, which was just barely open enough inside to shove the tent. I pruned a small path in from the south, to keep the access out of sight of the bike path, and tried to feel at home again.

In May I finally finished the book, ending up a novella. It was a relief. I’d never toiled so hard or so long on a written work. Hell, I even wrote a letter to the protagonist, as if she’d been real.

The publishing process can be slow, but I at least got Too Many Bigfoots on the market, at first only on the publisher’s bookstore. But soon globally.

While I worked on editing Bigfoots, another story came to me, and I had no choice but to write it. This became the first draft manuscript of my first-ever novel. Its original form, once I’d written the final sentence, was 80,000 words long. Just about right for a first novel.

So now that project loomed large, as well as my intention to write more short fiction to eventually publish in another collection.

But life sure has a way of laughing in the face of all your plans, hopes, dreams, and ambitions.

Part 2

Over the weekend of June 7-8, we had our first heatwave of the year. On the east side of the Cascades, we’re the “dry side” of the mountains. Even right up against the foothills, The Dalles is desert-dry, literally getting no more than about 15 inches of rain a year. Some years more, some less.

Humidity is always quite low. This heatwave saw not just 100 degrees on the peak days, Sunday and Monday, but the humidity dropped down below ten percent. It bottomed at about five percent.

Those low humidity levels dried out burnable fuels quickly. Tuesday was only five degrees cooler. I felt little difference between 100 degrees and 95. All the fine fuels were crispy. The heavier fuels were ready to burn.

Wednesday.

I’d finally gotten my laptop screen fixed after being without it for a year. It was hard to save up $300 for the repair, but after some months of diligence and some unexpected but very welcome charity, I was able to afford it. I wanted to give it a whirl and recharge some devices, so I decided to use the library’s isolation booths to get some overdue work done.

Just as I headed out with my laptop in my backpack (didn’t want it banging around in the bike bags– no suspension!) I had to, as usual, crouch to drop my storage unit door.

A year before, crouching to pick up a stone had sent my low back into instant agony. I could barely walk and ended up in Urgent Care after three days of horror pain.

This time, my lowest low back again went OUCH. This was almost as bad as last year’s pain. But I had no choice. I got on the bike anyway and gritted my teeth through the agony. I had important work to do, and had just gotten the damn laptop back after a year. I refused to cave to the pain.

Two hours at the library later, finished, I ran a quick errand getting some jugs of water and a basic lunch. I went through the routine at storage, loading up the bike bags and trading my nice clean “town clothes” to less nice or clean “camp clothes.” I usually backed the bike into the unit to load, and so I hadn’t peeked outside for a good 45 minutes.

When it was time to wheel the bike out and round up my last few things, I looked north and saw the smoke column.

Crap. Another fire in the Gorge, and yet again in the area of Rowena just a few miles downriver. That place seems to burn a lot. And with extreme winds, on top of the super dry fuels, it was looking like a dicey situation. I had no idea how it would unfold, so I just went ahead and pedaled out to camp.

I had to assume that our firefighters would stop it fast, since they seem to always be right on these things within minutes. Despite their incredible efforts, deploying so many resources including aircraft so quickly, the screaming wind and the dry fuels were faster.

The smoke was already filtering through camp when I got there.

I tried to remain, but the air quality kept worsening and I was starting to not like it so much. I noticed ash and black bits in the wind, and small particulate drifting through my all-mesh tent. My eyes were burning and I coughed occasionally.

Despite my desire to remain, stepping out of my little thicket to check, the smoke looked bad. Too thick. Just judging by the smoke quality alone, it was clearly getting too close. I’d seen smoke like that back in my photojournalist years. It’s what you see at the fire front. I started hearing the unmistakable sound of firefighting helicopters and planes. Between the air quality, the smoke quality, and the urgent sound of the aircraft maneuvering, it was clear this was a serious fire.

Sirens sporadically sounded to my west. Several times I heard a loudspeaker, “THIS IS THE WASCO COUNTY SHERIFF,” the voice boomed, “THIS AREA IS UNDER” and then said more that I couldn’t understand over the howling winds. I knew the rest from experience: “Get out! Now!” Just across Interstate 84 on Highway 30 sat a small mobile home park, clearly being evacuated. The question, as to whether this was a bad situation, clearly had its answer. I had to leave.

What to take? I didn’t know if this spot would even get affected, or how the fire would behave. The most I could reasonably fit on the bike were a couple of the bulky camo sheets, which were sometimes hard to come by in local stores. Everything else was always in stock around town like the tent and sleeping bags. I did also round up all the tarp clips, since they cost $3 apiece and I had a dozen of them in camp.

I left my heavy stakes, the ground cloth tarp, the tent and rainfly, a sheet of camo, extra lines, the small memory foam mattress, two sleeping bags, two sets of cold weather thermal underwear, my pillow, a can of bug spray, a water spray bottle, and three gallons of water. I had allowed some bags of garbage to accumulate near my access trail, which were destined for the trash cans at the trailhead, but there was no room on the bike. I do keep a tidy camp, but I’d procrastinated and now I had to accept that the trash might burn. For someone who cares about the environment and leaves no trace, it stung.

I dropped the tent’s poles so as to flatten it, but I can’t exactly recall why I did that. Then I snapped a photo of camp, and started rolling video.

I wheeled the bike over to the rock knolls that overlooked the little inlet near my old campsite by the walnut tree, now back to full foliage in late spring. And watched, waited, while taking a bunch of bad videos of whatever I could document. Mostly just smoke and ash flying. Visibility was terrible, so I had no idea what was happening upwind.

My location was basically directly in the smoke column. The high winds blew grit and dust and ash into my eyes, watering them, and I coughed. The smoke thickened. Firefighting planes and helicopters circled, making passes at the fire and then returning to the airport in Dallesport to top up fuel or water, or dipping into the Columbia.

I held out as long as I could.

The phone told me that the area was now under Level 3 Red GO NOW! evacuation levels, but I’d lived in places where we were under the same levels and we stayed. Even when one fire sent flames within a quarter mile of the house, we stayed.

So I stayed.

The winds were certainly driving the fire ahead of its footprint, and I knew that a spark could ignite the landscape around me at any moment. I kept my head on a swivel and stayed vigilant. At one point the winds gusted so strongly that despite having two kickstands on my bike, it toppled anyway. My eyes and airways burned and I hacked. Blackened bits of burned things blew around, some small, some leaf-sized. Any one could still be live. Any one could spark fire right beside me.

I nearly left several times, but then the smoke would shift, revealing no fire nearby, and so I’d decide to stick.

But then at about six p.m., my worst fears came true. Through the smoke, not four hundred yards away I started spotting flames, some roiling ten, twenty feet in the air. Then were hidden again by smoke. Crap! So it had blown through the Discovery Center Museum property and was well past it already. Fast. Too fast.

Time to go.

My escape plan was to simply take the Riverfront Trail south, but if the way was blocked, I’d ditch the bike and go on foot. If that route was blocked, I’d ditch my stuff and jump in the Columbia. I can swim, and my stuff could be replaced.

It was a simple ride back to the roads, where I found everything had been shut down and I was the last person off the Trail.

At the closed River Trail Way intersection with River Road, I found the scene in town chaotic. Road closures, vehicles with flashing lights parked all over, traffic cones, signs already up. I stopped on the overpass over Interstate 84 and took in the scene.

Down the slope to the left at Highway 30, Sheriffs and others had the road blocked, and the westbound Interstate 84 onramps toward Rowena were shut as well. Semis were stacking up on the nearby frontage road of 6th Street, and the townspeople were in a frenzy like a swarm of ants.

Sirens broke out sporadically, the planes and choppers droned and thundered overhead, the huge smoke cloud loomed north of town, emergency vehicles raced here and there. I pedaled over to storage and made a call to the Mid-Columbia Center For Living, where I’d connected with some services to help ease the sting of homelessness, and even landed a therapist to help work through my PTSD and other issues.

Their Crisis Coordinator suggested I try the Red Cross Shelter, which had already been set up at The Dalles Middle School. I waited at the storage facility, within the Level 2 yellow BE SET evacuation level, watching the fire unfold via a clear unobstructed view across the nearby school grounds.

I put together what I thought I might need, especially if the fire reached town proper and I wasn’t able to return. Not much, in a pair of bike bags with the equivalent capacity of my daypack. My back still hurt too much to load it up with the actual daypack. And the building was all-metal construction, protected by pavement all around. Could still burn, but I had to just kind of hope, like everyone else who’d fled.

I waited until about thirty minutes before dark, past eight p.m., and finally headed over.

I was exhausted, but also terrified and anxious. Since this fast-moving fire had actually sent parts of western The Dalles into Level 2 evacuation levels, I didn’t have one hundred percent confidence that the shelter was far enough from the fire to not be evacuated itself.

A painfully difficult ride, with a low back screaming in pain, muscles shouting in protest from yet more biking, including the ascent up the hill to the Shelter, the day’s heat still dehydrating me.

Despite the best efforts of the Red Cross, things got a little hectic. It was just a lot of people showing up at once. They got me registered, and a cot with a new Red Cross-logo blanket in plastic. Since I had been afforded the chance at storage to round up what I needed, I was a little more comfortable than some of the people who literally fled with just the clothes on their backs.

A good 60 people slept in the gymnasium that night. People were whispering, talking quietly, being respectful. The staff of volunteers paced around, setting up cots, handing out blankets, directing people to food and water, restrooms and showers, even pet supplies that had already been donated.

Several people indeed came in with pets, most kept in crates. Apparently there had even been a turtle, but I missed seeing that. I did what I could to get comfy on a cot with no padding. A volunteer came by and gave me an extra blanket to use as a pillow, which greatly helped.

Thankfully I had earbuds to blast white noise overnight, because at least a half-dozen people were terrible snorers. Dawn came far too early, but I did manage to find a toilet to use away from the crowd and at least have a little dignity. It was lines of guys outside the stalls and nauseating sounds and smells in the men’s room.

Then went back to my cot to figure out what I was going to do. I did know that I’d need to get back to camp and see what burned. It was hard to think. But I did make a decision to check as soon as I felt up to it. There wasn’t much hope, considering the ready-to-burn landscape, as well as how close the flames had been when I fled.

I was homeless before, and now likely double-homeless. My area, where I’d lived a year and knew I could be safe there from the worst parts of the homeless scene in The Dalles, was probably gone.

Part 3

The very next morning after the fire, I simply had to know if it had indeed burned. Did it spare my tent? My thicket hiding me from the bad guys?

I was too anxious to just sit around. I packed up early at the Shelter, told them I’d be back in some hours, and headed to storage. No smoke plume roiled out from the edge of town. Clear skies and an everyday feel to the streets greeted me.

We knew the fire had been stopped and the town saved, but so soon after, no one knew the full extent. The storage facility was open for business. Across the soccer fields the outcome was obvious.

I dropped off most of my stuff, grabbed a quick few shots of the freshly burned hillside, loaded up a minimal kit and and pedaled toward camp. Highway 30 was still closed at the overpass, but everything else was open. Gone were all the cones, signs, vehicles with flashing lights on the city streets and roads.

I rounded the Google data center and reached the burned area at about 8:30 in the morning. Hoses lay on the bike path; the fire had been stopped just at the center’s property line. Blackness patched the ground, interspersed with white ash.

I biked through the damage, smoke still pouring off spots, flames still crackling. My tire track was the first track of any kind in the ash on the Trail. So I’d been the last one to leave, and the first one back. My reward was discovering it had not been spared.

One would think there would be a moonscape of nothing, but I think that because of the severe winds, and the lack of heavy fuels, a surprising amount of things survived. But a great deal did go up.

Smaller trees were gone, but larger ones only bore charred trunks and crisped lower leaves, their crowns still green. The fire really had moved quickly. A large amount of the grasses and the blackberry thickets had simply vanished. It was a strange sight for someone who’d walked and biked this part of the Trail hundreds of times. I hardly recognized the place.

And as I crested the hill near camp and looked, sure enough, I’d had no luck.

The trail passes under a rail line just before you ascend the hill to the trail’s terminus at the museum, but shortly past the tunnel, down and burning debris told me to go no further. I started rolling video and shot this clip as I left:

I didn’t even stop. Just looked sadly and pedaled on. There was nothing I could do, and nothing for me there anyway. I could clearly see that it had all burned.

Birds chirped an indignant return, and a pair of pelicans were floating on Taylor Lake, a small mostly stagnant lake just north of The Dalles along the bike path. Conservationists had installed utility poles in the area with setups on the top for birds of prey to build nests upon; the osprey-occupied nest along the Trail in the fire zone had toppled when the pole burned. Its butt end, sticking up into the air, was still on fire as I passed.

I’d sent the video to a local reporter and he described it as “surreal.” I agree, it felt foreign, strange. The areas of moonscape, just fluffy white ash, only increased the sense of unreality.

So that was that. My home was gone again.

I had no idea what do to. And found myself distraught.

I mean, come on. I lose my place to live. I end up living out of a converted trailer. I have to sell the trailer and live out of the vehicle. I lose the vehicle, end up on the street. Someone robs me of my house and bed. I move to a safer area, and reside peacefully for seven months, it nearly gets mowed down, and then barely a month later, fire takes it.

Can I get a damn break here?

The anxiety, the unknowns. Where would I go? I’d searched the city for a safe, hidden spot to camp, but to no avail. That’s how I’d ended up out there near the lake along the bike path. It was the only place that made sense and offered the security and stability a person needs to have a home. While I felt high distress about my situation, I felt it even more so in response to the stories of disaster and tragedy all around me, people who’d lost it all not even twenty-four hours ago. Their sense of despair absolutely washed over me. I was heartbroken for them.

Later that day, while resting on my cot in the Red Cross Shelter, I got a text. I’d been estranged from my dear mother since February 2022, and despite having exchanged a few snail mail messages since December, were still not in contact. I mailed her thumb drives with copies of my new books. Every dedication page reads the same, and always will on every book I publish: “For mom, and for grandma.” But that was the extent of our relationship.

Mom texted me, clearly not knowing about the fire. She just said I’d been in her thoughts lately and she hoped I was doing okay, and sent her love. On Tuesday, the ninety-five-degree-day before the fire, I had mailed her a birthday card and a thumb drive with a copy of Bigfoots on it. But it hadn’t yet reached her. So she wasn’t responding to that.

She just knew.

I think that’s amazing. They say a mother always knows, that her love crosses any gulf, even the galaxy. And here right in a very difficult situation, she somehow knew I needed to hear from a loved one. The best loved one. I mean, what’s better than mom? Other than maybe grandma?

I really needed to hear that right then. And it was beautiful. We had a short text exchange, and she signed off with her love, and saying that I could text anytime. Communication lines open. I got my mom back.

The fire took, but then gave.

At first in the Shelter there were others, but after a few nights, I was the lone occupant. It was kind of odd. Rows of empty cots, all the donated supplies, just sitting there. I don’t want to say it was a waste; over the days people filtered in and out, staying a night or just popping in looking for supplies.

About fifty-six homes burned in the fire, and nearly one hundred other structures. Several days in, the water systems were found to be contaminated, and so even up at the shelter, the drinking fountains were covered with signs. I was told to not use the showers.

They actually ran out of bottled water for a few hours, while people sporadically came by looking to restock theirs. Someone located 85 or so cases of bottles and we were topped up by the afternoon.

The hardest part was being in the midst of a real disaster. Sitting there, hearing the many heartbreaking stories. People coming in, desperately grateful for anything, even some KFC meals from the day before which were technically leftovers. All they had were the clothes on their backs, literally, and the car they used to flee.

My senses of compassion and empathy are quite keen. I struggled to hold back tears many times, hearing people talk about their horror escapes. Some people vainly tried to fight the fire, to stay and save their homes, but when the fire burned the power lines, well pumps in Rowena went silent. Some survivors were white-haired seniors. That one hurt worse, seeing grandma and grandpa going through such trauma. I wept for them.

One man came in looking haggard, exhausted. His little dog, just a wee thing (looked like a miniature Doberman) was so distraught he couldn’t leave its sight for even one second without it barking for him to return. Since animals are not allowed in the shelter sleeping area or the cafeteria, the dog had to stay in the only viable place left: the locker room. The poor guy had to sleep in there with his companion, but at least they were together. He left the next day.

Despite having not lost my actual house and all my belongings, I still felt horrible. Many moments I simply broke down. Again, it wasn’t just about me. Seeing so much tragedy right in front of me, feeling their pain exquisitely, just tore me to pieces.

All the usual things happened, the waves of exhaustion, fear, anxiety, worry, anger, depression. The sleep disturbances, nightmares. Not being able to think clearly, feeling lost and pointless. Directionless. I had no idea what to do next. The staff ordered out for our meals, and I was a pain in the ass choosing my order because I was struggling so hard to stay focused. My mind just wanted to run in all directions.

Never in my life had I fled a wildfire, nor had I lost my home. It may have been a tent, but what that area out there offered me, in the security, the sense of home, having the ability to keep a stable living situation, allowing me to focus on my writing career, was every bit as valuable to me as a house. I could give myself a lifeline out of homelessness.

Had I been bouncing from site to site, or in a dangerous encampment I would be fighting for survival each day. Writing, or being able to stay on task and keep the goals in mind, were the gift that my little area out there offered.

Without that, how could I get back into a mental place proper for doing good work? Hell, I’d struggled badly enough in the public library with the over-the-top noise and disruptions. The cops were there at least weekly for dangerous or problematic people. I’d blasted white noise in my ears, and managed to get some semblance of work done.

But now with my laptop finally repaired, I’d only need a place to plug in. No longer dependent on public computers, and all their various limitations.

The PC was quite helpful in the Red Cross Shelter, offering the distractions of getting started writing this piece and getting to know my digital workspace again. And the Shelter’s places to plug in and keep things charged were a rare treat. Plus showers, food, toiletries, water; the volunteers really made sure anyone who showed up had all they needed, and were up to date on what to know. It was the best I’d lived in a long time. Indoors. Safe.

On the Monday after the fire, I had an appointment with my therapist. I finally let it all out, after putting on a brave face for days. I sobbed for a good five or ten minutes. Thankfully they keep a closet full of tissues.

The day prior I’d met with and Oregon Department of Human Services Disaster Recovery Coordinator who got right on the job seeing for which services I could qualify. Being homeless, and not having lost my actual house, I knew I was kind of a low priority, which I understand. But he treated me no differently. Compassion, respect, dignity. He connected with my therapist, who did some social work herself. Now I had a team of two working in the background to connect me with resources.

Someone emailed me about an Air BnB, but I thought, you know– there are people affected by this fire who’ve never been homeless. They just lost their home. The shock of becoming homeless is horrible, traumatizing. I’ve been through that already. Back in 2021. It still stung, but the initial pain had eased.

I wanted that rental (offered free of charge of course) to go to a family who just lost their home, who needed a place far more than some homeless guy. As an avid outdoors lover, camping is something to which I’m accustomed; living homeless meant camping out for several years on end. I had long since soured on camping ever again for recreation, but at least I was inured to the hardships and had the skills and knowledge to meet the challenges.

There was also the fact that I may have been in the upper class of homeless, but homeless of any class are the lowest class in society. I was the lowest priority among the fire victims, and I understand that, I get it. But given what I’d experienced the past four years, including recently, couldn’t just once I get a break? Maybe be allowed to at least get in line, even if at the back?

The ODHS worker did reach out to a local homeless shelter situated in a converted motel. Like many places, if not most, they had a wait list. At least, as a fire victim, they did push me to the top of the list. But, as one may stay in “The Annex” for up to one year, I had no idea when the next tenant’s time would be up, or when they’d transition someone out into housing and open a room. I couldn’t count on it, or plan for it. I was still on my own.

Really what I needed was housing. Finally.

But dammit, there were fifty-six families, homeowners, seniors even, who just lost their home and, in my opinion, should be served first above me. I wasn’t trying to play martyr, rather, I just felt it was the right thing to do.

These are people. Human beings. Regardless how it’s almost a fad to not care about anything or anyone in the world today, I’m cut from older cloth, a different fabric of society. I cannot turn my back on someone in such a dire time of need, or shove them aside to get served first.

No, I’ll go back to sleeping on the ground with ants and earwigs crawling all over me, if that means a grandmother gets to sleep in a bed tonight. And I won’t be asking for a damn medal. Knowing grandma is warm and safe is reward enough. Giver her the medal just for being grandma.

Another aspect of the disaster that really got to me was the level of community support. I think more people showed up to the Shelter just to donate or ask what they could do, than actual fire victims. People gave, offered more they could bring, told Red Cross volunteers of all the things they had on offer, from places to stay to animal supplies to water, even toys and games for kids. A row of tables was set up to hold all the stuff.

Someone sent stacks of pizza from Domino’s; pallets of water appeared. All sorts of things started appearing, like bags of dog food, baby diapers, toiletries, clothes, hell, I even spotted a kit containing a tourniquet and forceps! A woman came by saying her yard was now an overflowing repository of donations and we were free to show up and take whatever we needed, even posting a flyer with her phone number and address, just to make sure. Someone handed me a $20 Dutch Brothers gift card, reminding me that they sell a few food items. Other locations popped up, a local gym. The food bank.

There was too much to leave out on the tables so Shelter staff kept the food offerings to more reasonable selections spread out on the cafeteria tables. Surprise met me when I was in the cafeteria kitchen reheating some KFC in the microwave and I spotted all the rest of the food. Piles of it all over the counters. Bags of chips, granola bars, power bars, fruit strips, fruit, crackers, sodas, more waters, even candy. One night I simply snacked for dinner, rounded out by Trubars to nibble along with every flavor of both SunChips and Quaker mini rice cakes.

That no one needed the Shelter after only a few days also meant that everyone had either gotten a motel, or more likely had found a place to stay. Friends, family, that Air BnB on offer.

I get emotional even now acknowledging the fact that the community flung open its bedroom doors and pantry doors and closet doors, even wallets, and let everything go that was needed to go. And still, weeks later, kept them open.

Even for a “lowlife homeless” like me.

I have to say, after living on raw oats, peanut butter crackers, and protein bars for breakfast and dinner, and for months and months, my stay in the Red Cross Shelter was a culinary dream. They ordered out for most meals, offering me whatever I’d like from the restaurant they chose. It’d been years since I had restaurant food, and I’m being literal. I couldn’t dare spend that kind of money on meals on such a tight budget; expenses and bills like the truck’s storage fees ate hundreds as it was. And outdoors living requires all sorts of random but constant little purchases.

Maybe once a month at most I’d treat myself to an $18 lamb wrap from our local food truck the Shawarma Hutch, and it’s so damn good even now my mouth waters for it. The best food in town, many agree.

So being served a personal pizza -which I didn’t have to pay for- treated me like a king. I was so excited, the staff said I was like a little kid. I mean, you go without pizza for years, and see how you react when you finally get one.

Then it was Hawaiian. I didn’t even know we had that cuisine in The Dalles! And then we did Mexican one day for both lunch and dinner; I stuffed myself with a fajita bowl for lunch, and then carnitas (oh my fav!) for dinner. The final meal I enjoyed greatly, a lunch of sliders with fries from a local pub.

Until the water issue, I was having showers every day, a very rare treat for me. Normally my bath was a dozen or two wet wipes. I finally didn’t have to pay for food or water (no spigots in the blackberry thicket). I was indoors, though with the gym’s A/C stuck on low, a bit chilly. Gone were worries about where I’d charge my phone or other devices, like headlamps or backup phone batteries.

Every night in camp I’d have to pull security, never fully sleeping deeply other than on accident. Every sound must be paid attention to, every snap of a twig. Is it a deer just moseying through, or a tweeker trying to sneak in and steal my bike? Or a mountain lion? Unlikely, but you never know.

When that aforementioned motel shelter, The Annex, was under renovation, workers showed up one morning to find a cougar sleeping in one of the unfinished rooms. This is downtown The Dalles, just down the street from the Post Office, one block from the Chamber of Commerce, two blocks from the Police Station.

The worker slammed the door shut, trapping the cat, and the authorities darted it. I seem to recall they went ahead and euthanized it, since they worried it had become too used to people. So my fears about big cats in town were not irrational.

It was a relief to have the security in the Red Cross Shelter– four walls and a roof, and a night shift that stays up to keep watch and be there for anyone at any hour.

Those people are just so amazing. What I found the most inspiring was their ages.

Almost all of them were senior citizens.

Instead of settling down in the armchair and letting life end in front of a TV, these people haven’t slowed down or stopped. Age is only a number. One man was even a great-grandfather, of adopted family. His compassion for others was astounding. As with all the others.

They care. Really, fully, truly, care.

All my needs being met was their concern. Patient, attentive, communicative, listening.

I had a moment during breakfast one morning, and a volunteer was there, having accidentally brought up something painful for me. He apologized, but stayed seated, saying he was there to listen. I managed to not cry, but he didn’t care how I fell apart. He stayed there until I was done.

They all do this.

And the amazing part is how everyone speaks quietly. Low voices, whispers even. Gentleness. A light touch, but an effective one. The sense of peace and reverence for those going through this, made things so much easier.

I had felt quite uncared-about for years. That a group of people, knowing fully I was a homeless, didn’t judge. They knew my story, that my encampment had burned, and that I had already been homeless. I was still welcome to everything on offer with no guilt, no strings, no conditions.

These people are saints. And tougher than me.

You see, they can be deployed globally, if they choose to sign up for that service. The great-grandfather had only done the U.S. but had been there in Hurricane Katrina, one of the worst hurricane disasters -and the costliest at $170 billion- in the country’s history. People are still struggling to recover fully.

Another lady talked about being deployed to Syria. Then the front lines in Ukraine. If anyone incurred PTSD, it’s certainly her. But she still smiled, offered whatever service she could to others, and stayed bright and positive. Such an inspiration!

The fire had been basically out since the second day, and only backburns and mop up remained. As the days passed, the evacuation levels slowly decreased, and the Shelter remained empty save me.

While people were beginning to be allowed back to their homes or burned properties, “my” area was still closed. The Riverfront Trail needed its own attention to make it safe again for people. Mainly getting possible tree hazards down and putting out any remaining hot spots.

And even if I could go back, the entire area was a sea of ash and blackened ground. Wind would kick up ash clouds, and everything including my clothes would get marred. We’d need a few rains to wash things down and soak ash into the soil.

And even so, all the vegetation that would hide my camp and keep it unmolested had burned away. So for the forseeable future I had no home.

And of course, with the fire down and resources being let go, worse and larger, more persistent fires, broke out elsewhere. I’d known the Shelter would have a life span, and I hoped it would be at least a week.

Part 4

On the Wednesday one week after the fire, the notice was posted in the hallway at the Red Cross workers’ desk: Shelter Closes at Noon Thursday 6/19.

So that was that. I’d hoped that I would be able to rest at the Shelter after a medical appointment Thursday morning, but it was not to be.

I knew I’d just about worn out my welcome anyway. Even so, the staff cared for me. They still offered me all the compassion and help they’d give anyone, even those who’d actually lost it all.

That these people didn’t treat me any differently was amazing. No one else in society had done so. I’d been mistreated and disrespected in so many ways and places merely due to being homeless. So it wasn’t something I went around telling most people. But the volunteers saw only a human being.

As one volunteer put it, my being there was like “a warm hug.”

It’s true. These Red Cross volunteers are solid gold. Or, as one volunteer also said, “hearts with legs.” Some of the best people I’ve met in a very long time. Their undying compassion and care for everyone who showed up was incredible, amazing, and inspiring. My outlook, my attitude, would have been in the toilet without such a buoyant sea of support to keep me afloat.

These people set the example, raise the bar for all of us.

You don’t need a red vest with a red cross in a white background on your body to do what they do. No excuse or reason is ever needed to do the right thing. To care for everyone, no matter whom.

When a seventy-year-old is willing to stay up all night on the overnight shift just to be there in case someone comes in at 3:00 a.m., then the rest of us have no excuse for our failure to lend a hand.

We all see it today, worse than ever in 2025: how little anyone seems to care. All the issues are everything today, but literally by this time tomorrow it won’t matter ever again, or even be remembered.

People only seem to care about what’s right in front of them, and even then, their interest has an incredibly short lifespan.

And the fire is still right in front of us. You can look out across town all over The Dalles and see that blackened hillside.

It’ll look like that for months, reminding us that the people who lost homes may not have rebuilt by the end of 2025. Insurance claims can work like that. Or maybe they had no insurance. We’ve all been cutting back a lot in these days of the $100 bag of groceries.

So I hoped that just this once, people wouldn’t forget only a week later, since the Red Cross Shelter had closed, and the firefighting resources were demobilized or redeployed elsewhere. The intensive news coverage had waned.

This won’t be over for the owners of those fifty-six burned homes. Not for a while. We need to keep up our efforts to support them, especially the seniors. Not everyone is as fit and capable as the Red Cross seniors, and no one should be left behind in the fire recovery.

Although the one person who is most likely be left behind is the single homeless man who lost his camp in the fire. I understand why. Homeless people aren’t people. I’d bet money that a lot of folks around here would have a fit if they heard a homeless person had used the resources for fire victims. As if I’d somehow scammed the system or faked it.

I too had to literally flee from the flames just minutes before they torched my home. And the outpouring of donations was so huge that places like the Elks Lodge had to publicly announce they were overloaded and could no longer accept more. And recall I was the only person in the Red Cross Shelter for the most part. There was actually too much stuff and they wanted me to eat or take everything I could so it wouldn’t go to waste.

And yes, they too are allowed to use the donations. And I kind of think they’ve earned it. There’s mountains of the stuff anyway, and it simply cannot all be carted around from disaster to disaster. It just goes to food banks or donation centers, or animal shelters in the case of the used blankets.

With a bag of chips picked out just for me, and my souvenir Red Cross blanket bungeed down on the bike rack, I took one last look at my temporary home for the last week, savored the memories of meeting all those great people, and mounted up for the ride across town.

I had to say goodbye to those wonderful volunteers, and I’m still quite sad about parting. It was a rare breath of fresh air, a revelation, to be there for those seven nights. My eyes were opened to so many realities I never even considered, or had been blocked from seeing by privacy needs.

No photos or video were allowed by the media of residents in the Red Cross Shelter, and so the public never saw what we evacuees experienced. How organized, clean, well-stocked, and supportive it was. As a former member of the media, I too had been under those rules and never once saw the inside of a Red Cross Shelter. And it makes sense. The last thing you want in the worst time of your life is someone sticking a camera in your face.

When I was a photojournalist I was sensitive to that. I did my best to never be intrusive or invasive, or sensationalizing. I merely wanted to use images to tell a story. To tell the truth.

Now that I know, I realized that I needed to tell this story. If I’ve never experienced this, then of course most others also have not. Pulling back the curtain and showing everything, I think, is important.

All too often in disasters we try to euphemize, to say things in nice ways so as to ease the sting. The media likes showing us the flattened homes and husks of cars. I’d like to see a Red Cross volunteer getting a huge hug from a fire victim instead.

That’s the real story. The people, not the stuff.

Belongings, aside from heirlooms, can be replaced. We don’t cry over the loss of someone’s bedding, we cry for the person because they now have no bed. It’s not the house itself burning down that hurts, it’s grandma and grandpa now suffering the horrible shock of homelessness. Of having to start over with literally nothing. Not knowing what to do next.

We need to remember that in any disaster, it’s all about the people, both victims and volunteers. It’s about the men and women who step in when everyone else flees. Who bravely enter life-threatening situations purely because they care. Who support the people enduring the worst days of their lives.

Around the planet, it seems there are more people than ever who are having those worst days, whose lives are being threatened. The world is pretty messed up right now. But it can get better.

We all need to care more, and keep caring. About people, not stuff. About each other, about our seniors, our kids, the disabled, and yes, the homeless.

And what of this now doubly homeless writer?

Part 5

I managed to get a motel room, amidst a busy week in town, with not just the fire sending folks into motels, but also contractors working on fire recovery, and then a youth baseball tournament. Tourist season.

Saving my quarters, I hand-washed a few things in the tub. The tee shirt I’d worn in the smoke. I didn’t get it soapy enough and it still smelled somewhat. It was triggering.

Sirens now sent me into alert, scanning around for a smoke column. When there was nothing, I slowly relaxed. But not for long. It seemed my eyes couldn’t help but keep looking for that fire scar as I rode around town on my various errands.

Not just my shirt, but my hat, bike bags, a jacket, and the camouflage material all got stinky. The burlap material of the camo absolutely reeked. Every time I smelled it I flashed back on the evacuation. The fire, just right there. I may have to throw the camo away. Not because it’s ruined; it’s just too vivid a reminder. A trigger.

It brought back all the tragedies to which I’d borne witness. This was damn hard. Only two options, wallow in misery or keep moving forward.

On the next Friday, June 20, just nine days after the fire, we few homeless unsheltered survivors were given a lifeline. The agency which runs the aforementioned motel homeless shelter also ran a facility called The Gloria Center, which also housed its local offices.

There they had a good twenty of the so-called “pallet shelters” which are just small ultra-basic boxes with roofs, kept empty save for extreme hot or cold weather events. We were offered one of those little shacks for the weekend, but had to leave by Monday morning.

In the meantime, we were told, social workers would be toiling to get motel vouchers for hopefully up to a month, but at least a week, thanks to a benefit of our various health insurance plans. Which I’d never heard about. Whatever, I’ll take it!

Inside, two fold-down sleeping platforms, some shelving, and the electrics. Four windows at least, so natural light inside made it feel less harsh. I really enjoyed that it was equipped with both heating and cooling, and outlets. I was able to bring the laptop and actually function normally in the many digital tasks I needed to accomplish.

Two or three others came in, as far as I could tell. One was a solo woman who already looked sort of homeless. The other made me cry.

There were numerous kind and generous volunteers who showed up to staff the place 24/7 though Monday, having set up large meeting room as a cafeteria for our stay. They were chatting with me as I walked in, and we encountered a man, resting at a table. His little friend on his lap.

The man and his dog from the Red Cross Shelter.

He looked about as haggard as I felt, and no better than when he’d first arrived at the Red Cross Shelter days ago.

We tried to laugh about the now better accommodations, with a thick mattress provided, privacy. Showers and toilets to yourself. Better than that gym locker room floor, eh? He at least laughed a bit. I like to laugh more than cry. And help people try to laugh when things are down. It just helps.

The dog, he then told us, was his brother’s. His brother died, and the dog became his. A living attachment to his sibling, a physical connection. And now the little fella had been uprooted from everything normal again. Its new owner, a dutiful and responsible man, had of course suffered terrible loss as well. You could just see the anxiety vibrating in that poor little dog. The sadness dripped off the guy’s slumped shoulders. I was glad to be led away to see my shack right then, because I was breaking down.

At least they were together. At least they still had each other.

The woman staying there also had a larger dog, and both dogs often barked. In other circumstances I’d complain, being more sensitive to noise than others due to my PTSD, but come on. Of course I said nothing, and was nothing but kind and friendly to both. And everyone.

I didn’t think a person could wear out the phrase “thank you” but I may have discovered the tipping point. I made sure to thank everyone, for everything, no matter how tiny. I thanked them for showing up, for caring.

After a few somewhat restful nights, Monday came too soon. That morning I had an appointment with my therapist that I really needed to make, I’m sure you’d agree. In my haste to be punctual I was heading out and almost ready to pedal away, but the staff caught me and said, hey you forgot all the exit interview stuff– your grocery store gift card, the motel reservation!

If I’d been rolling already I’d have probably flat-spotted a tire stopping at that.

Of course, yes, please, thank you! And indeed, a few questions later about their service, mainly survey-type stuff, I was handed a $50 gift card for the local Fred Meyer grocer, and informed I had a reservation at the local Super 8 motel next door to the grocery, check-in at three p.m.

Well damn, it’s like a faucet turned on.

I go so long with bad luck after bad luck ad nauseam, so much so that I end up literally in a fire shelter, and then the gifts suddenly start flowing. Like I said before, the fire took, and then the fire gave.

Housing options, real ones, not shelters, started to open up for me. None instant, but neither far into next year. I was moved up to the top of some wait lists and things started moving forward finally. Nothing “for sure” but at least I was not left just hoping. I got a tentative grasp on a life line, and it turned out there was someone on the other end of the rope. My five-year gap in healthcare had ended and progress on my mystery fatigue issue was being made; I’d even reconnected with my dear mother.

And the fire gave me not just a path out of homelessness and toward better health, but a different perspective on life, and on humanity. Like a lot of others, I’ve sure gone through my share of misanthropic moments, especially in recent decades. But then moments like this come along, and you forget all that darkness. You feel only light and love.

I know quite well that the fire recovery isn’t about me, but I experienced this, and from only my perspective. And I did have a rare perspective on some aspects of the fire, that in some cases no one else experienced, or even knew had occurred. And I really wanted to make sure those who stepped up to help in this disaster got their recognition and deep expression of gratitude from me, and everyone in the community.

And what’s next for me? I can’t say. There’s the first draft of a novel to start editing. I’m being prodded to get audiobook versions of my e-books on the market. Of course it’s a very good idea, but either I rent some hours in a recording studio or pay someone to make the audiobooks. I’d also like to get that short story collection filling up. Finally make progress on my health issues. And naturally I’m on the housing hunt as much as possible.

For now, though, I have shelter, food, enough funds to make it through the end of the month, and now a team of several people who are working in the background to keep balls rolling. Not just for me, they’re taking on all the fire victims, big and small, that need their help. Just like the Red Cross volunteers, or the many other people around the community that donated, stepped up, and showed up.

And for that, I’m more than happy to say thank you one more time.

– – – – –

Post Script

Leave a comment